Whither Comic Art...

...and George Lucas's legacy project.

This summer, George Lucas made his San Diego Comic Con debut. Yes, THAT George Lucas: the man who, since the release of STAR WARS in 1977 has done more for the pop culture celebrated by SDCC than any other (yeah I said it, and I stand by it Stan Lee and Gene Rodenberry) waited until 2025 to make an appearance. For what cause? What news bombshell finally prompted the great hermit to emerge? Did he buy back STAR WARS from the House of Mouse? Has he dreamed up a new era-defining saga to create in his ninth decade? Not quite. He built a museum.

Source: Lucas Museum of Narrative Art

For about 45 minutes, Lucas sat on a panel discussing the Lucas Museum of Narrative Art with director Guillermo del Toro (a board member of the Museum) and Lucasfilm designer Doug Chiang, moderated by Queen Latifah. He provided an explanation of what he means by “narrative art,” and confirmed that he has been collecting comic art since his childhood and has amassed a collection of about 40,000 pieces (including other forms of art) and sells nothing (now THAT’S a black-hole collection).

Lucas calls narrative art “the people’s art.” It’s not just comic book art, it’s comic strips (Alley Oop received a name check - when was the last time you thought about that guy?), and the great illustrators like Norman Rockwell. To Lucas, this art is integral to our understanding of who we are. He cites Rockwell’s Freedom from Want:

Freedom from Want at the Norman Rockwell Museum in Stockbridge, MA. Source: Author.

To Lucas, we gather at Thanksgiving each year even when we may not want to (Lucas’s characterization, not mine) because we’re prompted by cultural cues like Freedom from Want to sit around the table and gnaw on poultry together. Narrative art knits a culture together; it tells us who we are by telling us what we value. The giant Los Angeles-based spaceship pictured above will be a temple to the people’s art and its creators, most of whom Lucas believes haven’t received their due credit.

What will be on display at the museum? The panel was light on the details, but the following came up: the first Flash Gordon drawing (Flash Gordon was a key inspiration for STAR WARS so that seems fitting); original “Peanuts” sketches (not clear if these are the original strip art or unpublished sketches by Schultz - my guess is the former - original art for published strips tends to be more expensive, but Lucas can afford them); the first “Iron Man” cover (it might be this one by Gene Colan); and an original Jack Kirby splash from an early “Black Panther” book.

As details about the Lucas Museum trickled out over the past few years, particularly as some theorized that Lucas was behind inflation in art prices, comic art collectors have speculated about the museum’s impact on “the Hobby.” Some seem convinced that the Lucas Museum will draw new blood to comic art, elevating prices and allowing those who started collecting years ago to rest assured they’ll be able to cash out their collections at an even higher number tomorrow than today. However, I’m not so sure. Why?

All this has happened before, and it will happen again.

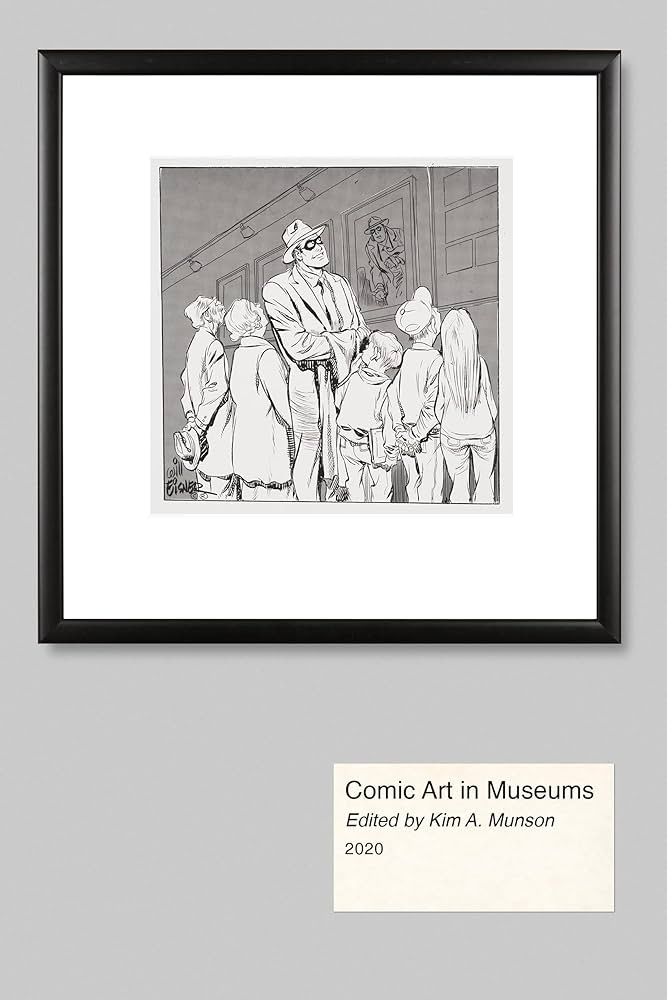

That’s what I learned from the wonderful Comic Art in Museums, ed. Kim A. Munson (2020) (the University Press of Mississippi graciously provided me with a review copy).

Available for purchase here. Cover image by Will Eisner.

In this Eisner-nominated anthology, Munson compiles writing about the public display of cartoon, comic strip, and comic book art (henceforth, I’ll use “comic art” as shorthand for these three disciplines) spanning nearly a century, from traveling displays headlined by Milton Caniff to international exhibits, and various attempts to establish and sustain dedicated cartoon or comic art museums.

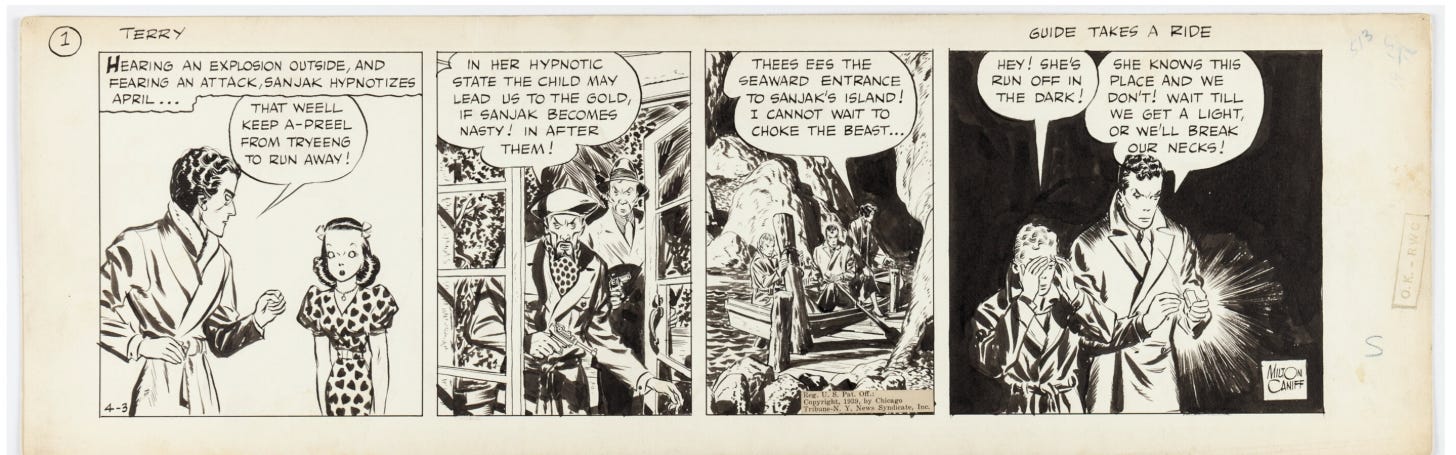

A Milton Caniff/Terry and the Pirates original, published in 1935. Source: Heritage Auctions.

Munson’s work allows us to situate the advent of the Lucas Museum in a historical context, and, I think, should inform the analysis of what impact the museum will have (if any) on the Hobby. Bottom line: I’m pessimistic.

The road that brought us here is littered with prior attempts to establish museums dedicated to comic or cartoon art. Many have not withstood the test of time. Munson includes Brian Walker’s (son of museum founder/Beetle Bailey creator Mort Walker) fascinating recap of the history of the Museum of Cartoon Art/National Cartoon Museum/International Museum of Cartoon Art, which shuttled from Connecticut to New York and ultimately to Florida before it closed in 2002 and its collection merged in 2008 with the Billy Ireland Cartoon Library & Museum at Ohio State. Munson herself interviews Joe Wos, founder of Pittsburgh’s ToonSeum, which shuttered in 2018. Other “historical” museums in a list Munson provides at the back of the book include Geppi’s Entertainment Museum in Baltimore, Maryland; and the Museum of Comic and Cartoon Art, which has been absorbed by the Society of Illustrators. Some common denominators:

1) Operating a museum is really hard

Walker’s description of building and running the Museum of Cartoon Art includes problems with renewing a lease, tracking down a new location, moving a massive collection across state lines from one home to another, and renovations carried out by armies of volunteers on a shoestring budget. Wos describes the challenges inherent in dealing with the public, and marketing a museum’s offerings to attendees. Obviously museums with institutional backing - the Billy Ireland at Ohio State, the Butler Library collection at Columbia University, and now the Lucas Museum - probably have a better chance at longevity than the independent joints, but still, running an arts institution is tough sledding. Why?

2) Comic art in museums is a tough sell

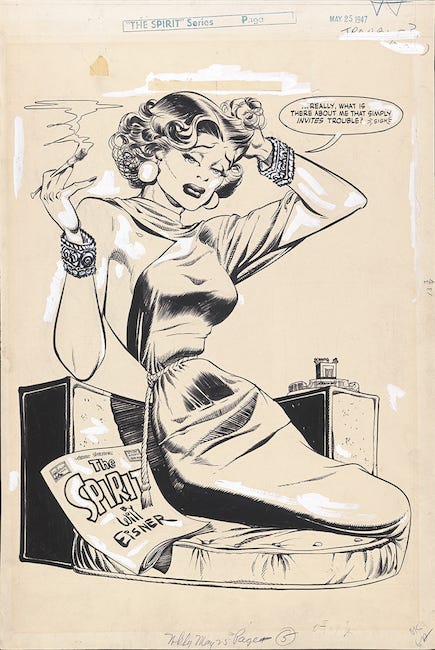

The comic art generally displayed in museums is the instantiation of an intermediate stage of an industrial process. What does that mean? It doesn’t display very well. It’s typically on 11x17-inch art board (although older pieces were done at a slightly larger size), so you need to stand close to the art to make out the details.1 White-out, blue-pencil marks, pencil lines that did not get inked, margin notes, pasted lettering, and Zip-a-Tone all might adorn a page of original comic art and testify to changes to the art throughout the creative process that culminated in the printed work.

Splash from The Spirit, ©Will Eisner Studios, included in an essay by Denis Kitchen as an example of the “warts and all” nature of original comic art. Source: Artforum.

To connoisseurs, these marginalia and seemingly minor details are a feature, not a bug. But to the casual museumgoer (or board member considering an exhibit of comic art), I fear they could detract from the apparent value of the object. Who wants to see the wires behind the magic trick? Do we really want to pay attention to the man behind the curtain, or just buy in to the illusion? Here I see similarity to movie-prop collecting. Most are happy to enjoy the finished product: the film. Only a small fraction of the film’s fans are invested enough to want to know how the product was put together, down to the specific type of camera flash used to construct Luke’s lightsaber (a Graflex 3, for those who care).

Speaking of finished products: my favorite entry in Comic Art in Museums is an essay titled “Permanent Ink: Comic Book and Comic Strip Art as Aesthetic Object” by art historian Andrei Molotiu. In the essay, Molotiu puts his finger on an issue that has bugged me as a fairly new collector: how do you display this stuff? A comic book page on a wall, divorced from the context of the story told by the surrounding pages, becomes something else. Molotiu:

[T]he shift of attention that takes places [sic] in the move from the book to the wall - toward form and materiality, away from story - does not completely negate the page’s narrative content, but reframes it. The narrative is fragmented, and the act of exhibiting a single page creates a sense of mystery as to the specific events portrayed….

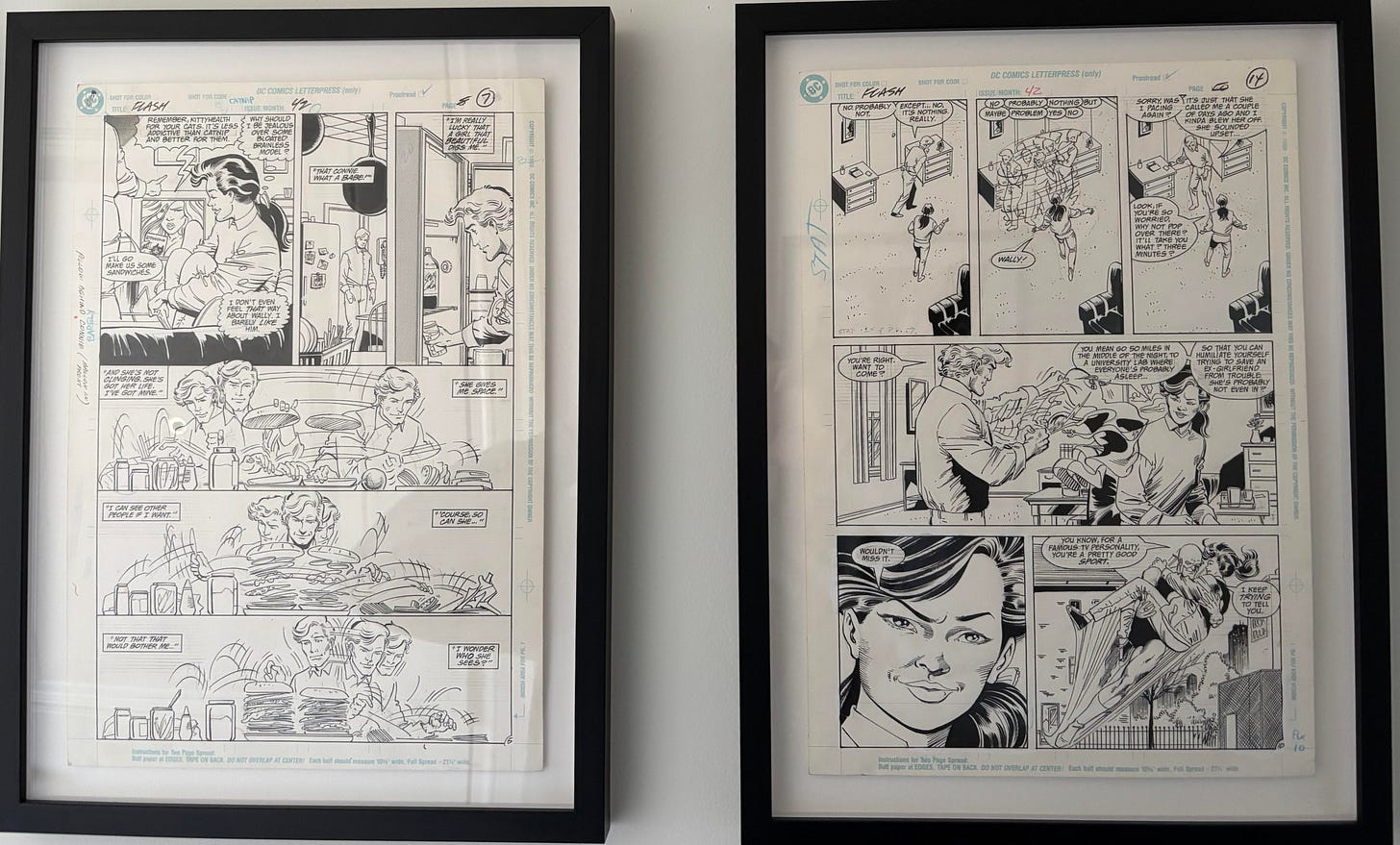

For example: I own pages 7 and 14 of The Flash #42. They were the first original art pages that I bought:

The Flash #42, pages 7 and 14. Greg LaRocque (pencils); Jose Marzan Jr. (inks); Tim Harkins (letters). Source: Author.

I didn’t read the book before I bought the pages; I just liked the Flash, thought it would be cool to have pages with the Flash making a sandwich, and liked the middle and bottom right panels on page 14. After I received the pages, I read the book, although it’s practically unreadable. But that doesn’t hinder my enjoyment of the pages. I enjoy the motion lines in the sandwich-making panels, the copy-pasted stats in the panels at the top of page 14, and the inkwork in the bottom left panel of 14. I’d rather live in the “sense of mystery” Molotiu describes, and imagine where the Flash is off to next than situate my art in the narrative of the actual comic book itself. Owning and displaying the original art compels me to slow down and find joy in the smaller details.

Unless you’re a far more moneyed collector than I am, you purchase pieces individually, rather than buying complete books (although art reps will sell you complete books if you’ve got the cash). Some collectors opt against framing their art, for fear of sunlight-induced fading. Others, I think, prefer the feeling of flipping through art much like they would flip through the finished comic. Storing and displaying art in a folio keeps the art closer to its narrative roots. Ultimately, I think it’s a matter of taste and preference for the individual collector (I do both, mostly because we lack much space that is almost entirely protected from direct sunlight).

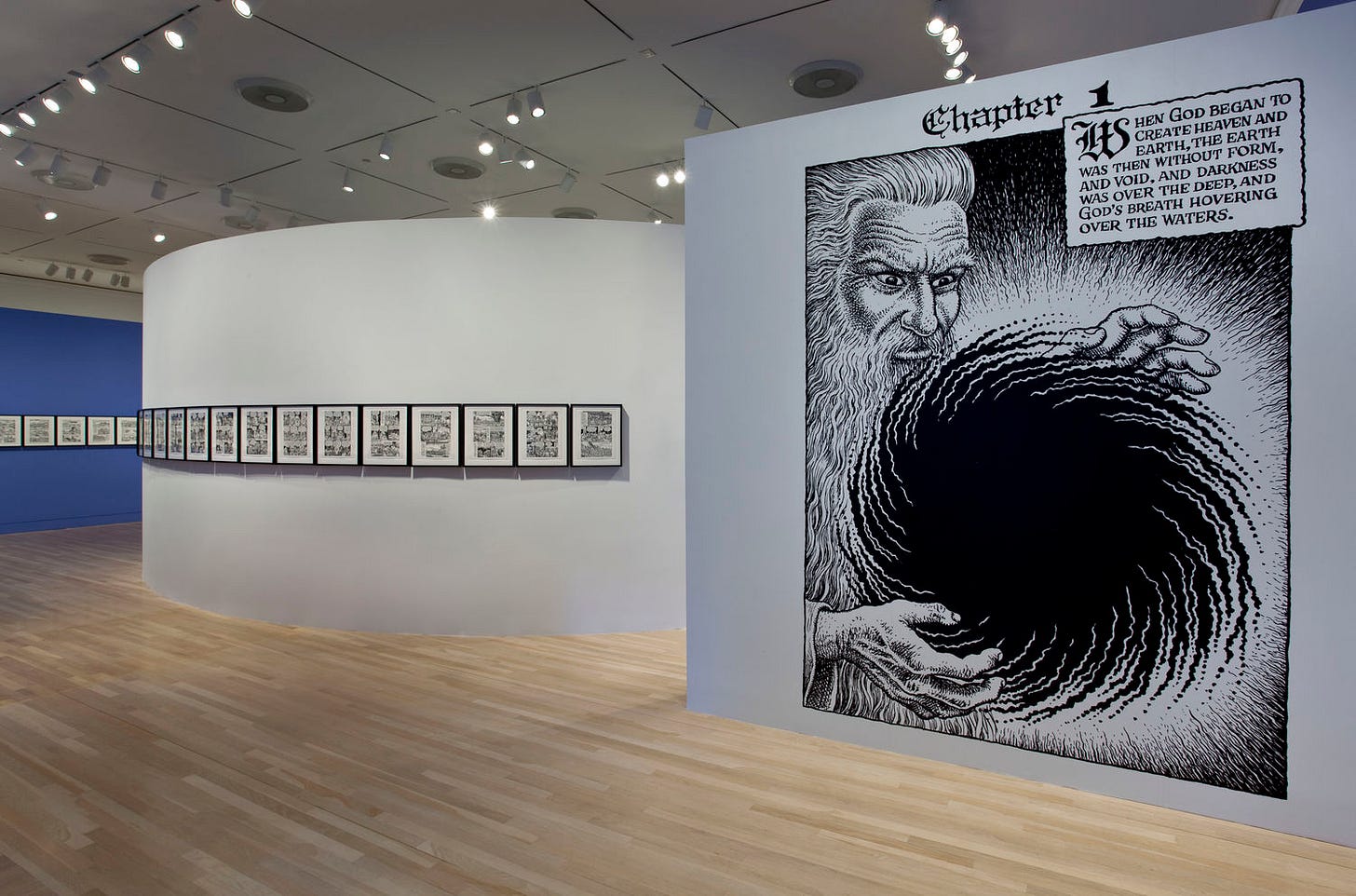

Museums displaying comic art must contend with this issue, and have addressed it in different ways, from “gallery comics” that are purpose-built for display in a gallery or gallery-like setting, to the UCLA Hammer Museum’s display of 201 pages of The Book of Genesis drawn by comix pioneer R. Crumb (recounted in Comic Art in Museums via a fascinating essay by Charles Hatfield).

How to display a narrative medium? One such approach, above. Some visitors made multiple trips to the exhibit because reading 201 pages while standing gets uncomfortable. Photo Source: The Hammer Museum.

If Comic Art in Museums has a weakness, it’s perhaps the book’s scattershot nature. There’s lots here, but I would appreciate more meta-commentary from Munson to tie the themes together. One particular area where I left wanting more was the formation of a comic-art canon. Museum curators who decide the artists and works that end up on the wall are incredibly powerful, especially in a niche medium like comic art. This is where I believe the Lucas Museum could have its greatest impact, for better or worse: the curators’ selection of works for display in the Museum or inclusion in its collection reflects a value judgment on selected (and non-selected) artists’ contributions to the medium. These curators will therefore play an important filtering role in shaping the public taste, and public understanding of who the important comic artists are.2 Comic Art in Museums makes clear that the comic art canon is anything but settled, and previous attempts to establish one have invariably been noteworthy more for their exclusions than inclusion, particularly their exclusions of women and people of color. To the extent that the Lucas Museum’s initial or permanent exhibits will draw heavily (or exclusively) from Lucas’s own collection, his personal tastes will have an outsize role in determining that canon. Who gets in, and who gets left out? I’m not saying they’re making the wrong choices, but they have to make choices, and those choices can affect the Hobby, in terms of our understanding of its history, and the prices for those artists who become “canonized.”

Wrapping up

I don’t want to imply that I am opposed to the Lucas Museum - I look forward to going! However, I do think that its impact on prices and participation in the Hobby is more likely to be modest than exponential. I doubt many people will visit the Lucas Museum, see comic art for the first time, and decide to become collectors. Plenty of attendees to the various comic conventions around the globe walk past or casually peruse art dealers’ booths; if that’s not enough to get them into the Hobby, why would the Lucas Museum? Munson’s anthology tells us that it’s tough to hit a home run with comic art in museums. Here’s hoping that the Lucas Museum figures it out.

I’m a lawyer, but not your lawyer. The views expressed above (“Views”) are not legal advice. Views are mine alone (and I don’t even know that I’ll stick to them, if pressed). Views should not be attributed to anybody else, including (but not limited to) my employer, employer’s clients, friends, family, or pets (current, former, or future).

Note that original strip art and cartoons are likely even smaller than comic book original art.

I acknowledge that, to the extent that prices follow perceived significance of an artist, the Lucas Museum could create an impact on art prices through its role in forming a canon.

Hi Nate, and thank you for the kind words about my essay! (And also greetings to a fellow original comic art collector.) I've actually done quite a bit of comic-art curating since Kim's book came out -- "Raw, Weirdo, and Beyond: American Alternative Comics 1980-2000" (co-curated with John McCoy) at the McMullen Museum at Boston College in 2022, and "Magic Ledger: The Drawings of Saul Steinberg" at the Eskenazi Museum at IU Bloomington in 2024. The former has a pretty big catalog too, if you're interested. I'm also curious what you thought about my "Afterthoughts" piece, which I wrote as an appendix to the reprint of my article?

Hey! Thank you. I just found your post. I appreciate your insights. I'm developing a follow-up book about curating comics that I hope will answer some of your questions. I go to San Diego Comic-Con every year and saw the Lucas Museum presentation. I was relieved to hear all the panelists talk about the importance of comics, so I hope they will find a regular place there. I wrote a book chapter about the exhibitions of Lucasfilm, which is the concluding chapter in the academic book "Lucas: His Hollywood Legacy" from University Press of Kentucky (2024). I researched the establishment of the Lucasfilm Archives and discussed the major US shows. I talked with people at the Lucas Museum, but was ultimately not allowed to use anything. I did see the SDCC panel the curators did a few years ago, but that was all the info I had, so that part was a little disappointing. I do think that folding Comic Art into the larger category of Narrative Art might help it get more traction.