Media & Memory

An Ode to Trash Culture and the Pack Rat

Long time no write. Sometimes a guy’s gotta recharge and regroup, figure out what the next topic is going to be. Here’s one that I’ve been mulling over for a minute…

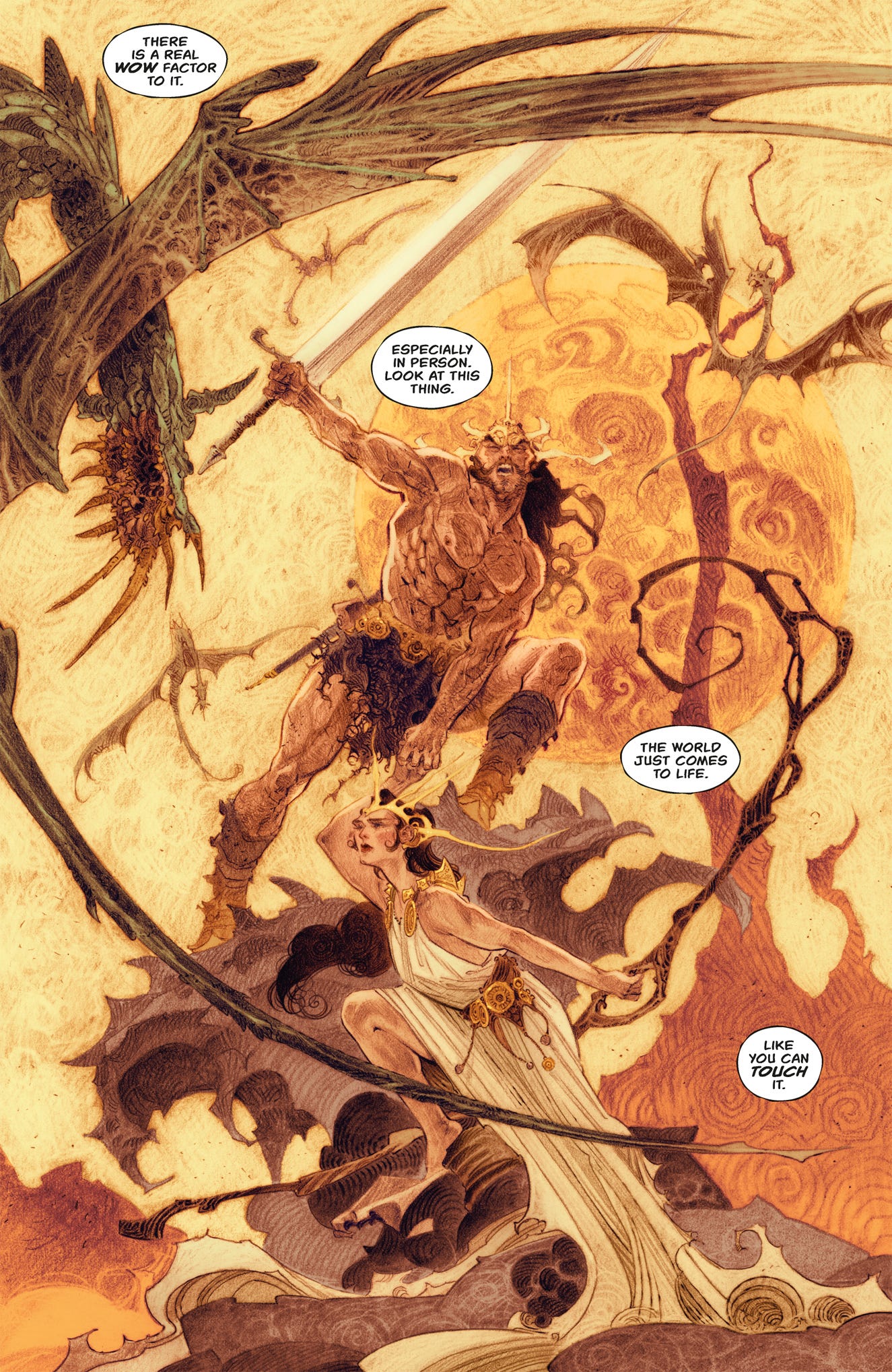

HELEN OF WYNDHORN. I spent much of my time off around the holidays dragging Colleen to various comic book stores, hunting for the early issues of Helen of Wyndhorn, a six-issue miniseries written by Tom King, drawn by Bilquis Evely, and colored by Matheus Lopes.

I’ll set the table with the sales pitch provided in advance of issue 1: "Following the tragic death of her father C.K. Cole, the esteemed pulp writer and creator of the popular warrior character Othan, Helen Cole is called to her grandfather's enormous and illustrious estate: Wyndhorn House. Scarred by Cole's untimely passing and lost in a new, strange world, Helen wreaks drunken havoc upon her arrival. However, her chaotic ways begin to soften as she discovers a lifetime of secrets hiding within the myriad rooms and hallways of the expansive manor. For outside its walls, within the woods, dwell the legendary adventures that once were locked away within her father's stories."

THE ART is glorious. Bilquis Evely’s lines are delicate and magnificent, and Matheus Lopes’ coloring makes the work sing (first time I’ve ever shouted out a colorist, that’s how good it is!). I reached out to Evely’s art rep, who told me that they’re planning to display the art in gallery shows, so as far as I know, none of it has yet hit the market. I’ll be there when it does, likely priced out of the hunt, but a guy can dream…

THE STORY is all about memory. Helen’s holding on to her memories of her father, somebody whose work ultimately becomes well known, but who, personally, was an unknown to all but her. He reared his daughter across Texas, and King sketches enough of the man for us to imagine him keeping the two of them on the road, one step ahead of creditors or even the law, for quick-talking rapscallion’s offenses like hustling pool or kiting checks. She knew him, but nobody else did. She drinks to forget that his suicide robbed the world, her world, of him, and the saddest part of it all is that nobody except for her will remember.

King frames the story by putting us in the shoes of Helen’s former governess who is approached near the end of her (long) life by a fanboy-biographer of C.K. Cole. The biographer records their conversations on a series of tapes that later get passed around (presumably following the biographer’s death), from the auction block to an afterthought at a convention (“hey buddy I’ll throw in a box’a these tapes”). Nobody, not even her grandson, is interested in (what seems to them to be) the deluded rantings of a senile former governess.

Cole is obviously based on Robert E. Howard, creator of Conan the Barbarian: both Texans, both committed suicide in their 30s. Howard was an author for the pulps: cheap magazines meant for mass consumption. He never saw it, but his barbarian of Cimmeria ultimately became a feature film (helmed by John Milius, one of Schwarzenegger’s early roles, with James Earl Jones as a villain), comics, t-shirts, video games - the gamut! All from a few stories in a disposable medium. It’s funny, the things that stick with us, and the “trash” culture that lingers.

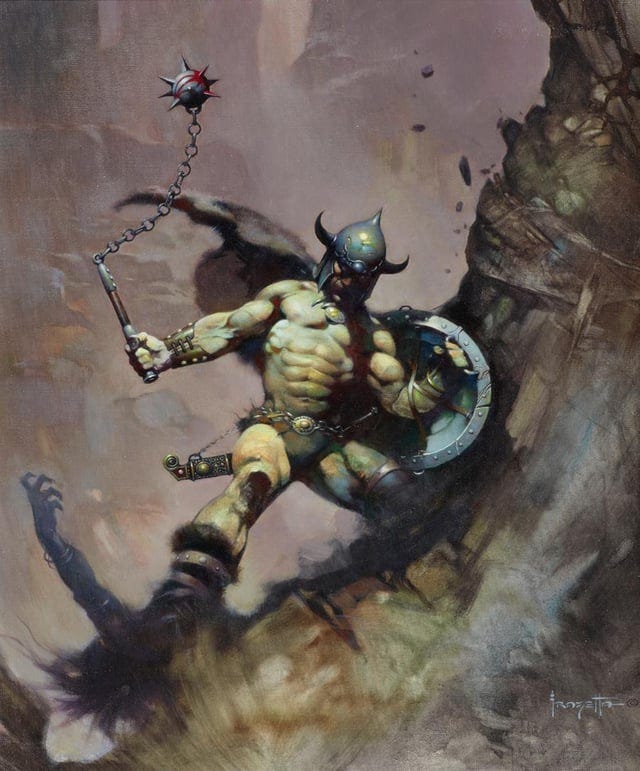

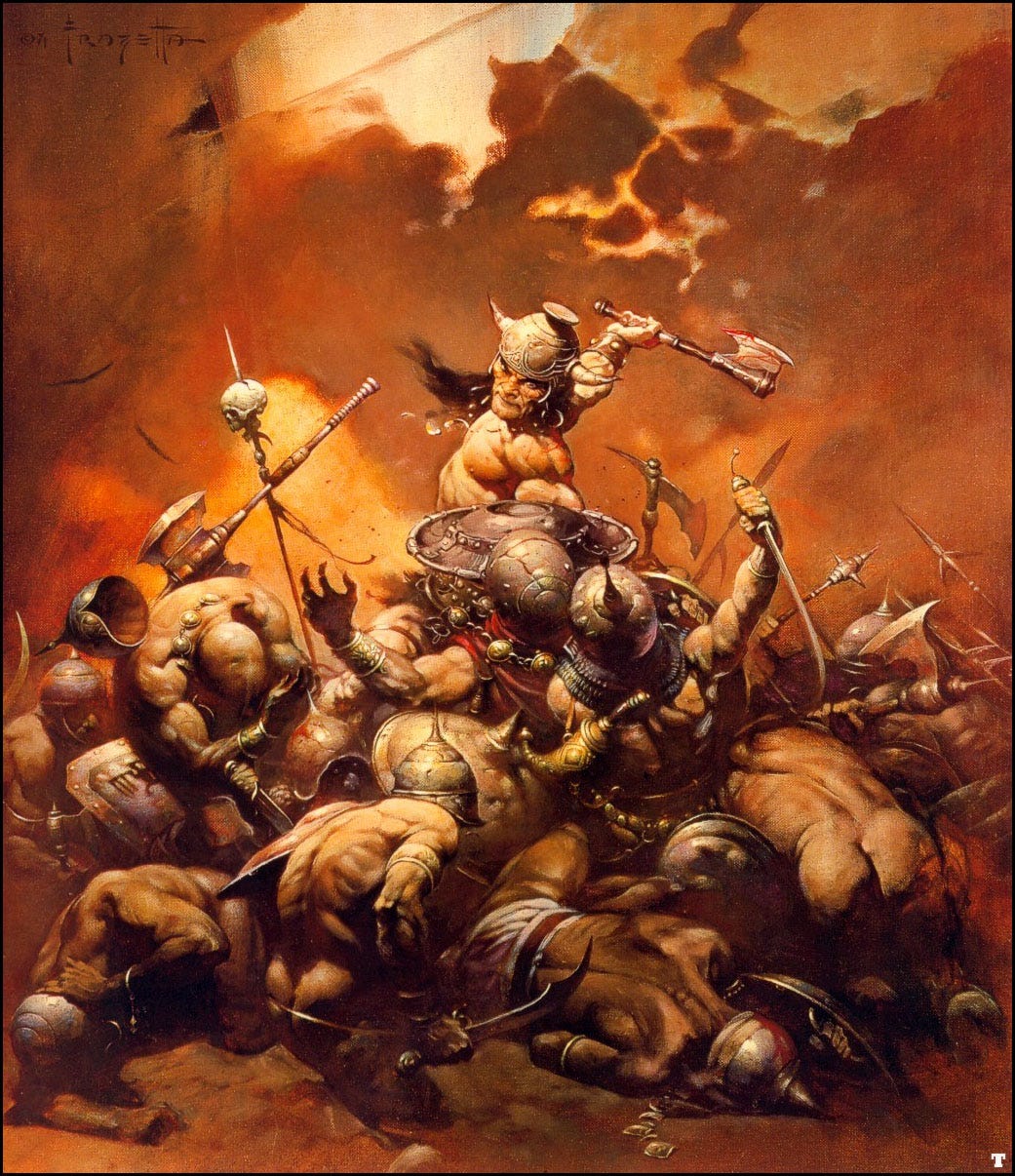

ONE OF THE REASONS why Conan enjoyed a resurgence, and such popularity amongst the boomer crowd are the covers to Conan novels painted by fantasy artist Frank Frazetta. Chances are pretty good you’ve seen a Frazetta painting somewhere along the line, chances are 100% that you’ve watched or read something influenced by him.

Frazetta, Warrior With Ball and Chain (1972)

You can learn more about ol’ Frank from the 2003 documentary Frazetta: Painting with Fire (available on Amazon Prime). It’s worth a watch just for the murderer’s row of artistic talent (Dave Stevens, Neal Adams, Brom, even Glenn Danzig of The Misfits!) who line up to testify to Frazetta’s impact on disposable culture. According to the doc (and no way is this an unbiased look; the only question it’s interested in is “Frazetta: Great or Greatest?”), once Frazetta’s work started covering the Conan novels, they started selling like hotcakes.

One of the film’s concerns is the lack of acceptance of Frazetta as a “serious” (i.e., fine) artist. He doesn’t have a museum, nor are the reigning fine-art museums clamoring to exhibit him; the film ends with the opening of his own place, on his own property, in the middle of Pennsylvania. The Met’s a long way from East Stroudsburg, PA.

And why shouldn’t he be in the Met? Yeah, he was doing narrative art, but (the film responds) what is David’s Oath of the Horatii, or the Met’s own Washington Crossing the Delaware if not narrative art? Frazetta brought a unique vision to pulp scenes. When he paints a battle, you feel the intensity and the chaos. Rothko wanted viewers to feel something too. So what’s the difference?

Frazetta, The Destroyer (1971)

Price, for one. For the price of a single maybe-da Vinci, you could probably purchase most of Frazetta’s output.1 But Belloq said it best (words I never thought I’d write): take a $10 watch, bury it in the sand for a thousand years, it becomes priceless. Who knows what will happen to Frazetta’s market years from now.

I’VE BEEN READING Quentin Tarantino’s excellent Cinema Speculation, a compilation of essays about films he watched as a youth in the 1970s, and the effect those films had on him then and now. The last chapter of the book isn’t about a particular movie, it’s about a guy, Floyd, who lived with QT and his mother for a year. Floyd wasn’t an actor or a director; he worked at the post office. He was, however, a MASSIVE movie fan, which was the basis of his friendship with Tarantino. He also dabbled in writing screenplays (never professionally), and wrote the first screenplays Tarantino ever read.

Tarantino, a pulp-auteur if ever there was one, waxes rhapsodic about a screenplay Floyd wrote, an epic Western about two cowboys called Billy Spencer. According to QT, winner of the Palme d’Or, and an Academy Award for Best Original Screenplay, “the essence of what Floyd was trying to accomplish in [Billy Spencer], an epic western with a black heroic cowboy at its center, was the very heart of what I was trying to accomplish with Django Unchained.”

Nevertheless, he continues, it’s unlikely there's a copy of Billy Spencer anywhere on the planet today. When Floyd died, whatever was left of the story was likely thrown in the trash.

What’s the answer? I don’t have one, just an observation: sometimes we overlook the value of the things that seem common, and are quick to discard them. Maybe it’s best if we just pile them up in the attic, and come back to them in a few years. There’s some really great stuff up there.

The views expressed here are mine alone (and I don’t even know that I’ll stick to them, if pressed). They should not be attributed to anybody else, including (but not limited to) my employer, employer’s clients, friends, family, or pets (current, former, or future).

Or you could trade a banana and a half for one of Frazetta’s iconic Conan images. Nobody ever said these markets made sense.