Over the past year or so, I’ve plunged into a new hobby: original comic book art. How’d that happen? I’ll try to explain in the next few hundred words, and expound over the next few entries.

It all started with a few trips to New York Comic Con, where I wandered past a few art dealers’ booths. Plastic bins overflowing with Itoya folios on tables separated the crowds from towering racks holding yellowing posterboard, a little smaller than a newspaper page, with prices reaching five, sometimes six figures. Usually the more expensive “wall art” is from the sixties and seventies, sometimes the eighties. Think Jack Kirby, Neal Adams, Steve Ditko, John Byrne, Frank Miller.1 In the barricade of Itoyas blocking the top shelf art from the (probably unwashed) masses is the comparably cheaper stuff, but it’s all getting pricier, honestly.

Jack Kirby Fantastic Four cover (sold at auction in 2021 for $480,000)

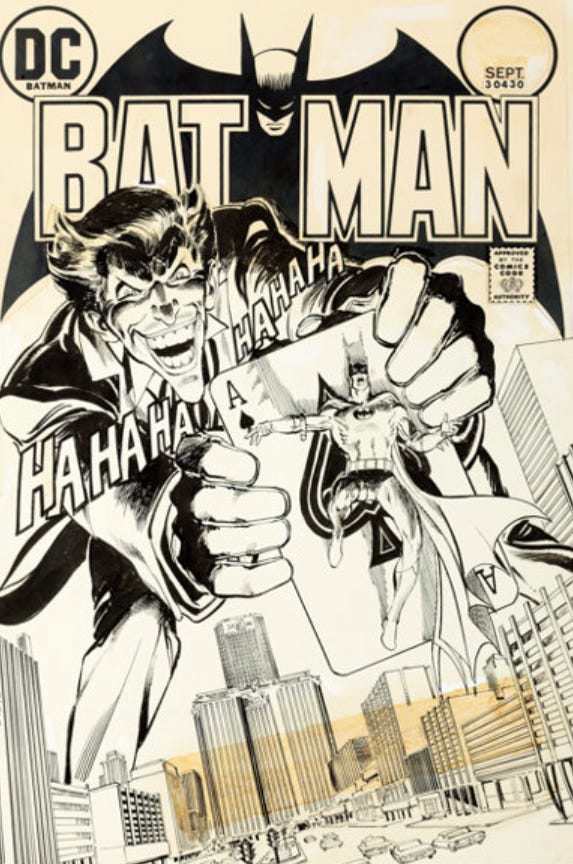

Neal Adams Batman cover (sold at auction in 2019 for $600,000)

In those folios, I could flip through work by artists like Dave Finch and Jim Lee, whose names I recognized from my personal golden age of buying comics from about 2003 to 2010.

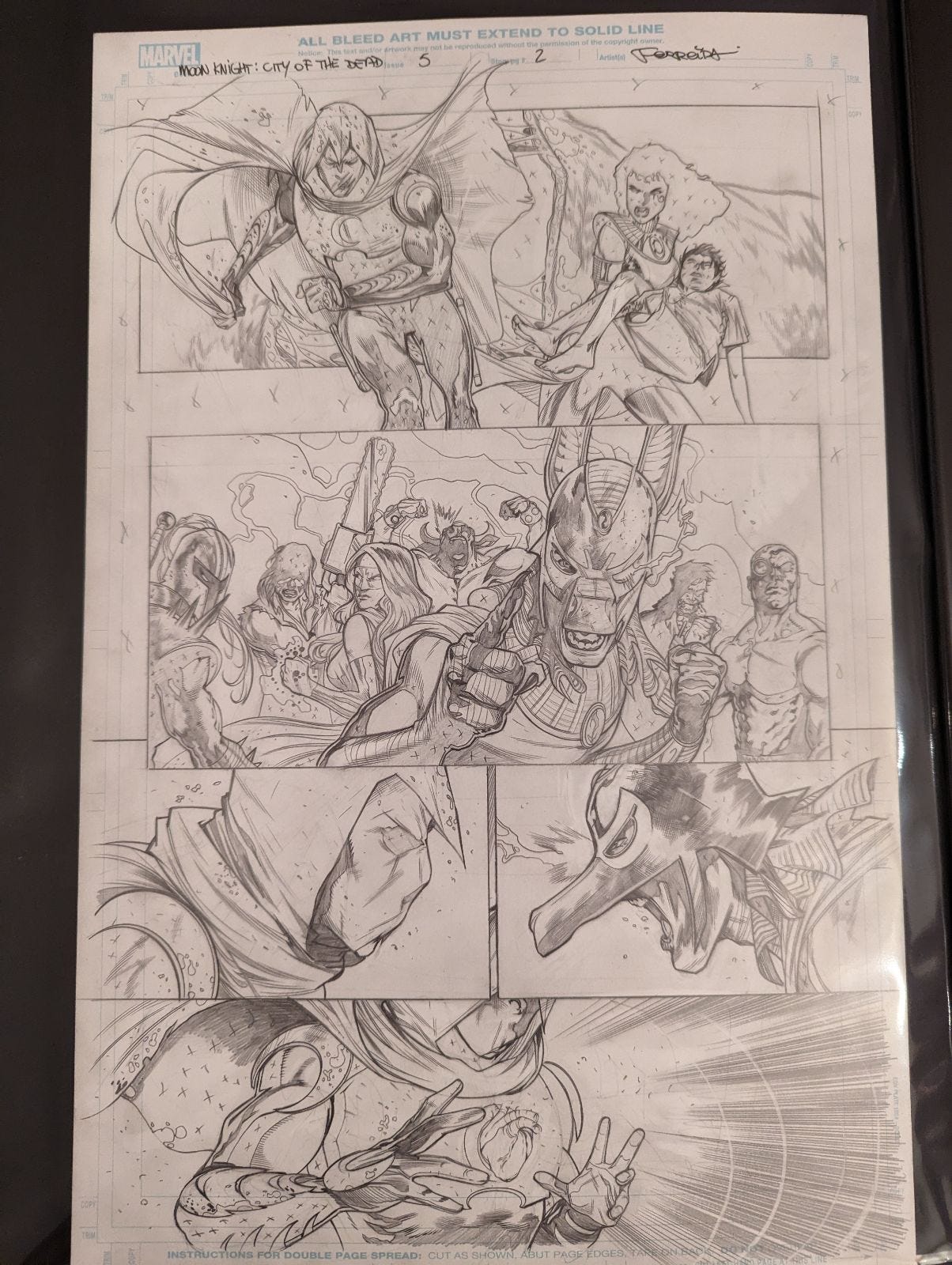

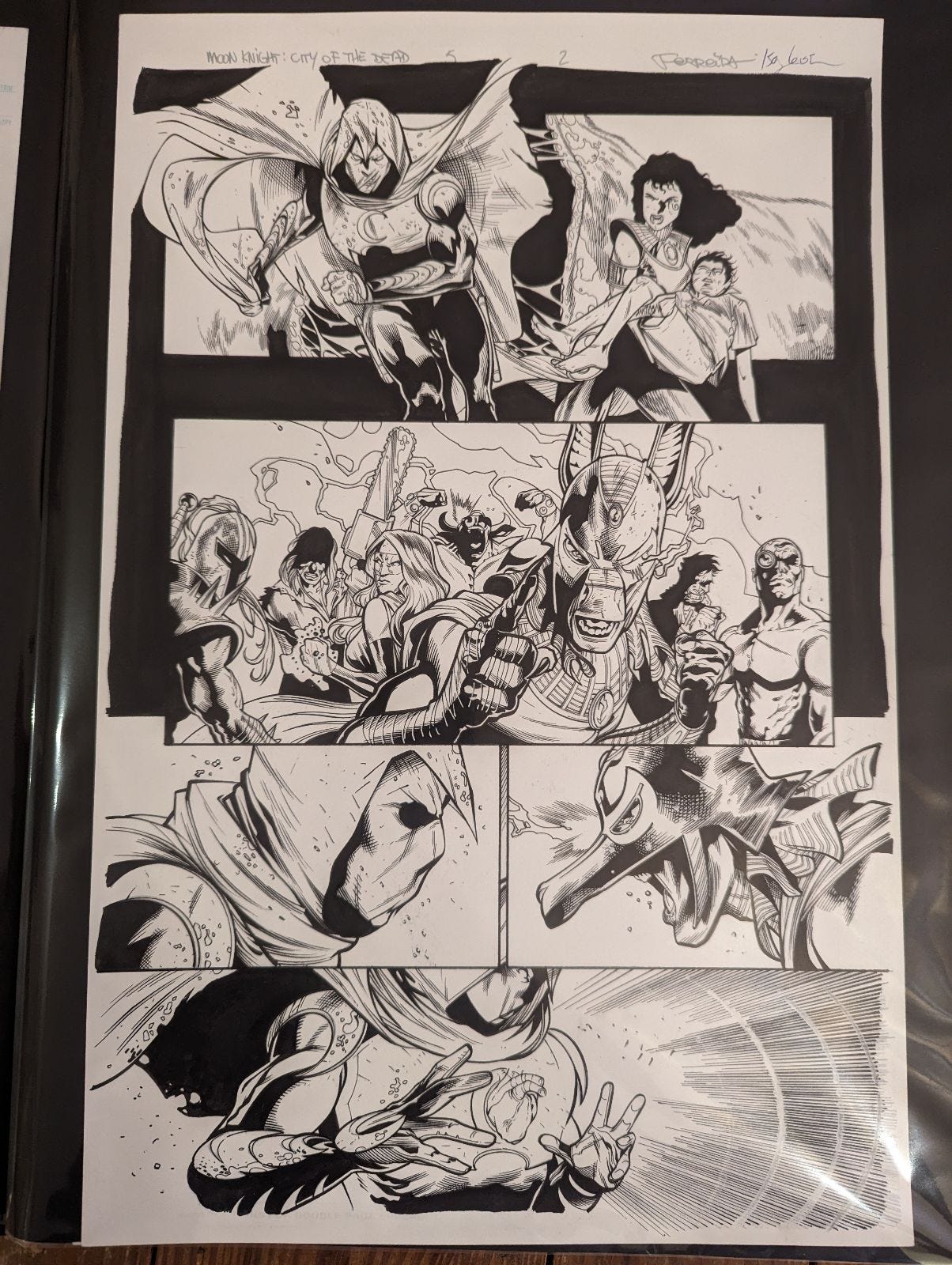

Panel page from artist Dave Finch’s 2006 run on Moon Knight (sold at auction in 2023 for $5,040)

As I looked through the original art, I noticed emblems of the art’s role in the comic book production process: hastily scribbled notes from an artist to an inker or colorist; brush or marker strokes where the inker laid down some heavy black ink; white-out over a patch to allow the artist a second pass at a tricky part of a panel. Some collectors dislike these foibles; they want the stuff where the artist got it right the first time. But those notes, and corrections are part of what drew (sorry for the pun) my attention to original art. It’s like watching an action scene in a movie: it’s cool to see the scene the first time, but it’s also fun to see the wires on the stuntman, and learn about how they did it. It’s just an opportunity to appreciate the craftsmanship that goes into the final work.

Then I started looking at the price tags. Comic art pricing is fascinating. During my travels through the pages, a few patterns emerged: covers cost the most, followed by the “splash” interior pages where a single panel dominates the page (there are also half-splashes, third-splashes, etc.2). Full-page “pin-ups” showcase a character, much like a splash (and the term doesn’t always carry the same salacious connotation in the comic art context). Equally relevant to a page’s cost is the character(s) depicted on the page: Marvel art tends to sell higher than non-Batman DC, and Spider-Man and the X-Men, especially Wolverine, are in the highest demand. Anything Star Wars, too.

Hot artists also drive prices. Those in highest demand tend to be the ones whose work was on newsstands when today’s collectors with expendable income were kids. That explains the astronomical prices for the work of all the greats mentioned above (plus a few more), but it also means that prices change as more comic fans discover original art, and pull together enough money to pay for it. Eighties art has been expensive for a while, but nineties art is climbing these days as nineties kids climb the income ladder. For now, stuff in my Golden Age of the early 2000s remains achievable, but we’ll see how long that lasts.

Some collectors look down on modern art. In part, it’s because the process for creating comics has changed since the halcyon days of Kirby and Ditko. Until about 2000, artists would typically draw the art for a book using pencils, and then hand it off to an inker, who would add shadows and depth using pens or brushes. Sometimes an artist would do their own lettering - the all-important word bubbles, the *BIFFs* and the *BAMs* and the *POWs* - but sometimes a separate letterer handles that step. Then the page goes off to a colorist, who colors a copy of the art (not the original) to provide the printer with a “color guide.”

In the old days, when most of the industry was in New York, an office boy could run pages from artist to inker around the office, or from one studio to the next. The big revolution came with scanners. Now pencillers can work from anywhere, then scan their work and email it to the inker. The inker prints off the pencils in “blueline” (blue scans differently) and inks over the printout, creating a second piece of “original art” for each page of a comic. Some collectors believe the pencils are the important half of these pairs, because the penciller usually does the work conceptualizing and drafting the page while the inker traces over the penciller’s work. Others think that the inked art is what was actually published (ignoring the fact that the colors and letters are added digitally), so the ink page is more important.

Marcelo Ferreira pencils (top) and Jay Leisten inks over bluelines (bottom)

An upshot of this change in production process is that the two pieces of art often wind up in different places, leading to a scavenger hunt across art representatives and dealers to reunite the pair. Just like primitive man hunted wooly mammoth, earlier this year I found myself hunting down the inks for a page of Marcelo Ferreira pencils that I bought. It didn’t take much; I pretty quickly found the inks on an art dealer’s website. Unlike prehistoric man, I negotiated until I won my wooly mammoth, and days later, it arrived at my door. The thrill of the hunt indeed.

Since those first con trips, I’ve tracked down artists on Instagram, haggled with art reps, and dipped my toe into auctions. While doing so, I learned a ton about how and why people collect. I’ve also thought a lot about how and what I should collect. Am I in it for nostalgia, for hype, for display, or something else? Part of the fun is the chase: figuring out who has what, and whether they’re asking a fair price for it. Hopefully now you understand the “how” of The Hobby - the “why” of it is a topic that I’ll leave for another day.

Kirby’s known for his work on books like Fantastic Four and Avengers. Neal Adams redefined Batman, Ditko was the first Spider-Man artist. John Byrne’s X-Men run is iconic, and Frank Miller defined Daredevil, then redefined Batman (after Adams).

The practice of terming pages “half-splashes” and “third-splashes” is actually kind of controversial in “The Hobby” because some think that it’s puffery that exaggerates the significance of a page.

That too!

“I’ve also thought a lot about how and what I should collect. Am I in it for nostalgia, for hype, for display, or something else?”

I thought it was to stop the shakes?