Two Reviews - Tiny Worlds

For some reason lost to history, the nineties were the halcyon days of movies about tiny people. Think about it: Honey I Shrunk the Kids and the subsequent Shrunken/Enlarged-Family Expanded Universe titles1; The Indian in the Cupboard; The Borrowers; Stuart Little (stretching it a little, but it’s my newsletter). Marvel realized there’s gold in them (tiny) hills, and gave us Ant Man et al., but the tininess was secondary in those movies, while it was the main event in their trailblazing predecessors.

What’s appealing about Tiny Movies? I’ll offer a theory: the worldbuilding is very easy. It’s already done for you, because it’s the same one we live in today! Just imagine the things that would scare the shit out of you if you were an inch tall - house cats, beetles, thumbtacks - and there’s your movie.

So imagine my surprise, my sheer delight, when two new comic books hit the stand, one, Mouse Guard: Dawn of the Black Axe, that I knew would be a banger, and another, Bug Wars, that looked promising. Both dig in to the Tiny World concept.

Mouse Guard: Dawn of the Black Axe (David Petersen, Gabriel Rodriguez)

David Petersen has been writing Mouse Guard stories for nearly twenty years. In his world, mice live a perilous existence in scattered colonies surrounded by danger: snakes, owls, crabs, and the elements threaten. The Mouse Guard and their teeny, tiny swords are all that stand between danger and their fellow mice. Key to the Mouse Guard mythology is the Black Axe, a weapon of totemic significance to the Guard and whose wielder brings salvation to mice in dire circumstances.

Mouse Guard: Dawn of the Black Axe tells the tragic origin story of the Black Axe, and of Bardrick, the first mouse to wield it. The book opens on Farrer, a blacksmith, lugging the axe to Lockhaven, home of the Mouse Guard. We learn that Farrer forged the axe as an act of mourning after his family was killed by a snake. Bardrick, a Guard Mouse, takes the axe (against the wishes of the Mouse Guard’s leaders) and swears to visit vengeance upon all the snakes threatening Mouse-kind.

It’s a simple plot that has some holes; instead of traveling south to battle with the snake that killed Farrer’s family, Bardrick travels north to fight some other snake whose relevance to the story seems limited to, y’know, being a snake. Nevertheless, it’s a delight to be back in Petersen’s Mouse-world, because there’s precious little of it; probably in part because for most of his earlier projects Petersen has tackled the entire production process - writing and art - himself (an anthology series excepted).2 Petersen is writing Dawn of the Black Axe, and coloring the art, while Gabriel Rodriguez has assumed penciling and inking duties.

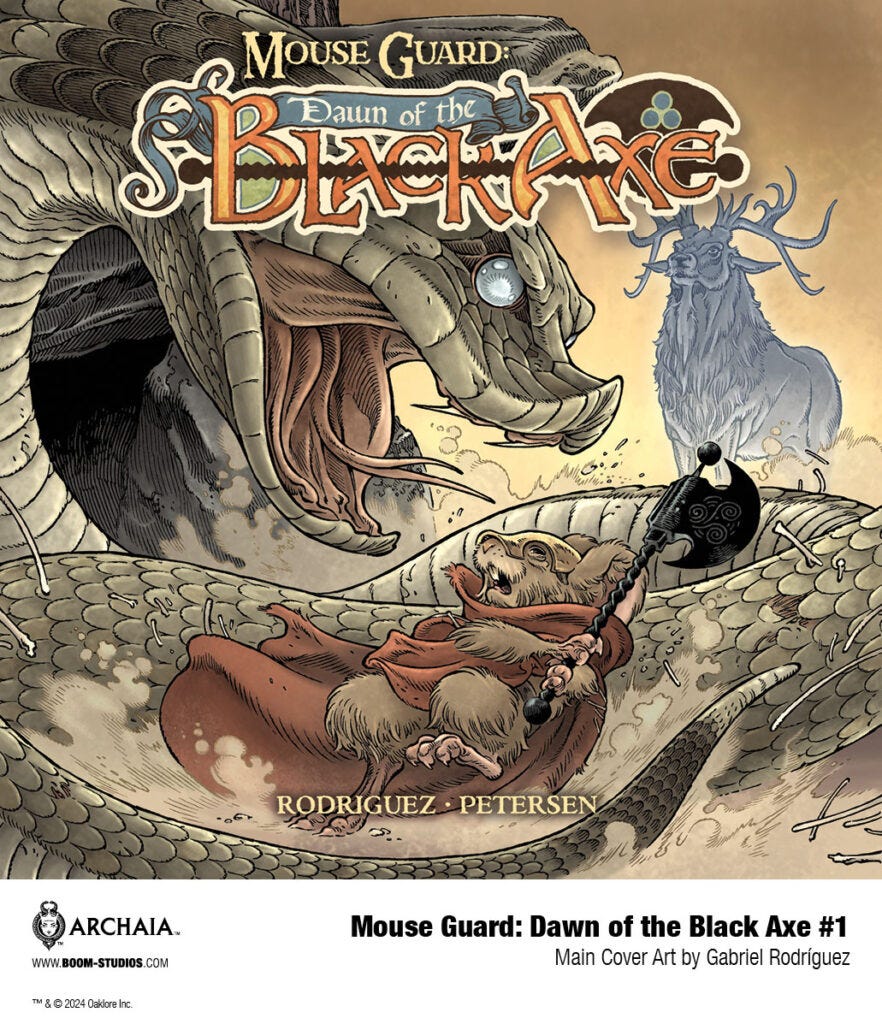

It’s a smart match. Rodriguez’s art (see the cover to issue 1 above) is perhaps a tad more fluid and commercial than Petersen’s, whose own work is informed by his printmaking background.

Petersen’s cover to the hardcover Mouse Guard: Fall 1152.

Nevertheless, with Petersen on colors, Dawn of the Black Axe has a similar palette to other entries in the series, and it all hangs together. It’s a delight to return to Petersen’s world, and I look forward to the remaining two issues.3

Bug Wars (Jason Aaron, Mahmud Asrar, Matthew Wilson, Becca Carey)

When I was little, my brother and I would build little villages out of twigs. We’d spend hours building big huts, little huts, water supplies, everything; an entire kingdom in our backyard.

That’s exactly what Jason Aaron is after in Bug Wars. Protagonist Slade Slaymaker is the son of a recently-deceased entomologist, and he, his mom, and his insect-hating older brother move back in to the family home after their dad’s death. With the assistance of a magic amulet (the least interesting angle of this story, if I’m being honest), Slade finds himself shrunk down to “myte” size, and embroiled in conflict among the various factions of insects. The Ant Imperium, the Beetle Clans (pictured below), bees, spiders; all kinds of insects have their own factions and homelands within the realm of The Yard. And all are pissed off at Slade’s older brother for mowing the lawn.

I don’t want to spoil too much, but if you want to recapture the feeling of limitless possibility an imaginative youngster associates with the backyard, this is a book for you.4 I’ve read much of Jason Aaron’s output: he has a dark sensibility that has taught me not to expect any mercy for his characters. Bug Wars is refreshingly unique, like Antz brought to you by Rob Zombie, and I wholeheartedly recommend it.

A double-page spread from issue 1, via Image.com.

I’m a lawyer, but not your lawyer. The views expressed above (“Views”) are not legal advice. Views are mine alone (and I don’t even know that I’ll stick to them, if pressed). Views should not be attributed to anybody else, including (but not limited to) my employer, employer’s clients, friends, family, or pets (current, former, or future).

Honey, I Blew Up the Kid (1992), Honey, We Shrunk Ourselves (1997), and Honey, I Shrunk the Kids: The TV Show. The original film came out in 1989, but close enough to the nineties. By the way, that movie made $222 million on an $18 million budget, so I think the reason for this trend may not be so lost to history

We came tantalizingly close to a feature film, but it was canceled two weeks before production was scheduled to begin. The would-be director of that feature, Wes Ball, posted a nine-minute pre-visualization video meant to capture the look and tone of the film.

For what it’s worth, I’ve also interacted with David at a con, and he was extremely generous with his time, even though I was a little starstruck. I root for any project he has going, so I’m not exactly coming in to this review as a totally blank slate.

Note, however, that this is certainly not a book for youngsters; salty language abounds, and for some reason, Asrar seems to be trying to sneak the odd bit of male anatomy into the art here and there.